Vehicle Access Fundamentals For Regenerative Landscapes – First Principles

Welcome To Vehicle Access Fundamentals

This series covers how to best lay out, construct, maintain and retrofit vehicle access routes for maximum function and minimal maintenance while repairing, preserving and enhancing ecosystem integrity.

Running water is the primary natural force that generates the need for maintenance of most man-made access routes.

Most drainage needs throughout the landscape are in relation to access routes. Effective drainage is therefore the primary consideration when planning and designing for functional, low-maintenance access (for vehicles, humans and animals) that maintains or improves watershed hydrology.

“A road lies easily on the land if it is located on a landform where it can be readily and effectively drained (neither too steep nor too flat); is functional when used as intended (class of vehicle, season and suitable weather conditions); has appropriate drainage features (closely spaced, properly situated and adequately maintained); preserves the natural drainage pattern of the landform; conserves water; does not cause or contribute to accelerated soil loss, lost productivity or water pollution; does not encroach on wetland or riparian areas; and is scenically pleasing.

A road is not easy on the land if it collects, concentrates or accelerates surface or subsurface runoff; causes or contributes to soil erosion; impairs or reduces the productivity of adjacent lands or waters; wastes water; unnecessarily intrudes upon key habitats, stream channels, floodplains, wetlands, wet meadows or other sensitive soils; and is aesthetically offensive.”

—Bill Zeedyk, A Good Road Lies Easy On The Land

When patterning vehicle access through a landscape and designing drainage treatments it is helpful to start with first principles.

Principles of Resilient Access Planning and Drainage Design

1. Stay High And Dry Whenever Possible

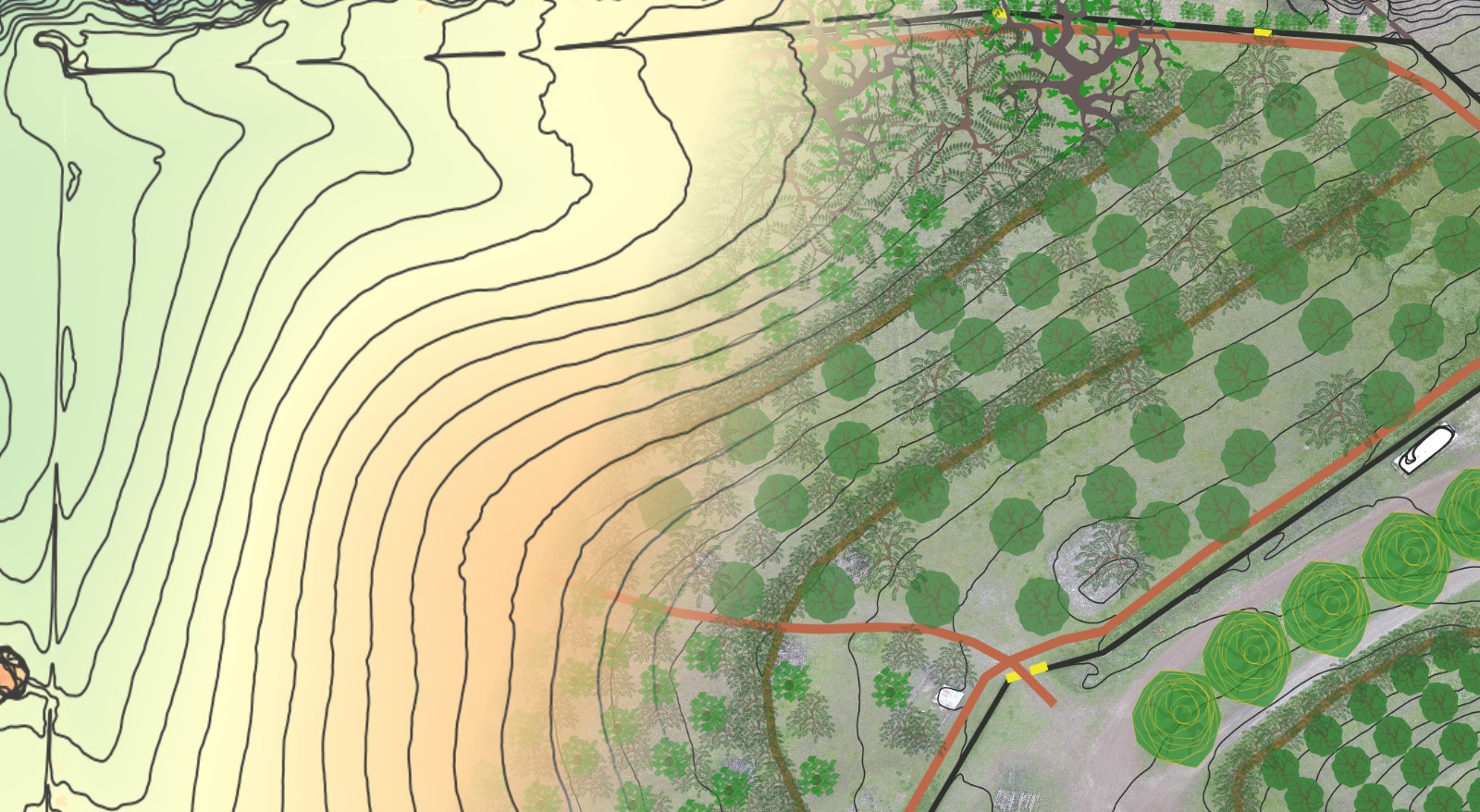

If you are installing a new vehicle access route where one does not already exist, when in doubt locate it higher in the landscape. Road surfaces located at relatively higher location in the watershed will inherently have less watershed draining onto them, and thus have less water to drain.

When possible, locate vehicle access along ridge lines, as the only water these roads will have to drain is what falls directly onto them.

Avoid placing roads and driveways in valley bottoms. Not only is there a lot of contributing watershed draining onto the road surface, there is often no good place to drain the water to! Valley bottom roads are notoriously prone to erosion. They often channelize water flows into narrow roadside ditches that then initiate large scale erosion processes (headcutting and gully formation) which accelerates the dehydration of the landscape above and below, in addition to threatening the integrity of the road base.

2. Use Grade To Naturally Drain The Road

Lay out your road or driveway to keep the grade in the “Goldilocks” range – where it is just right to keep surface run-off velocity easily manageable and allows a full range of drainage treatments to be employed.

Grades between 4-10% are ideal. Grades flatter than 2% are difficult to drain effectively, and are at higher risk of puddling and rut formation. Grades steeper than 15% will be difficult to navigate with 2-wheel drive vehicles in anything but perfect conditions and have greatly elevated erosion potential.

Use grade reversals to build proper drainage into the roadway from the start. For example, if a road has a 4% grade uphill, every 200-300 feet briefly reverse that grade by heading downhill at a 3% grade, then resume the 4% uphill grade. This will create “humps” (i.e. frequent changes from uphill to downhill, or vice versa) in the road that will naturally drain water from the road surface. Outslope the road slightly (2% minimum) at these locations to discharge the water off the road surface (so as not to create any pooling) and ensure that the receiving landscape is properly armored or vegetated (or both) to receive the water without eroding. Install proper lead out ditches to move the water well away from the road surface where it can be spread over a broader area.

3. Bigger Is Not Necessarily Better

Wider roads will catch more water, and thus necessitate more and larger drainage treatments.

Less water on the road surface = less pressure on the drainage elements.

Make roads only as wide as is necessary.

4. Road Longevity Is All About Water Management

The following approach to road drainage comes from Bill Zeedyk, author of A Good Road Lies Easy On The Land.

- FIRST CHANCE: Situations will arise where it is either infeasible or potentially damaging to sensitive ecosystems to discharge road surface run-off. In this situation, carry the water as far as is necessary and discharge accumulated run-off from the road surface at the first possible chance.

- LAST CHANCE: In situations where there is clearly no opportunity to discharge water from the road surface for a significant distance down grade, such as when entering and incised road section or on a steep downhill slope, discharge all accumulated run-off before entering this “no go zone”. This is the last chance.

- BEST CHANCE: Also known as the “Least Worst Chance”. In some situations, the only available discharge point may be less than ideal, while also being the only option available – i.e. spilling onto less-permeable surfaces. In these situations, choose the best (least worst) of the options available. This is the best chance.

- NO CHANCE: Sometimes there is no opportunity to discharge water from the road surface – such as after a last chance and before a first chance. In these situations we are forced to deal with larger volumes of accumulated water further down the drainage than ideal. These situations often necessitate expensive treatments, and are best identified during the planning phase and avoided if at all possible. In no chance situations it is very important to appropriately armor and stabilize the transport areas these larger volumes of water will pass through (i.e. rock armored roadside ditches, long culverts or drainage pipes etc).

5. Cross Valleys Perpendicular To Direction Of Flow

If crossing a creek using a drive through, always cross at right angle to the direction of flow in a shallow (riffle) zone.

Where and when it makes sense and is advantageous to build a valley dam, the top of the dam can serve as an excellent valley crossing.

Crossing a flow path at an angle is dangerous because the roadway can very easily become the new flow path and divert large amounts of water to places where it should not go.

When crossing drainages that flow seasonally or intermittently (i.e. not perennial creeks or streams), consider using an armored fill crossing instead of a culvert. Culverts are more prone to failure, and are guaranteed to fail when their proper function is most needed (i.e. heavy flow events), whereas a structure like an armored fill crossing will not clog and will maintain the water flow in a lower energy state, which will be better for the health of the watershed and the road bed.

6. Drain More Frequently On Steeper/More Fragile Soil Types

As a slope steepens, the velocity of surface flows will increase.

The faster water moves, the more erosive potential it has.

The table below gives maximum allowable distances between drainage treatments (try to space them way closer than this!).

“A more pragmatic approach to selecting drainage points is based on the principle of dispersing runoff at every opportunity along the way rather than at some predetermined spacing interval.”

– Bill Zeedyk

More opportunities for drainage off the road and away from the road bed is always better than fewer.

7. Choose More & Smaller vs. Less & Larger

Smaller drainage treatments that occur more frequently will be more resilient, less prone to catastrophic failure, and less costly in the long-run than installing less frequent but much larger drainage treatments.

Surface water run-off follows an exponential curve with regards to how much and what size of sediment it can move.

Don’t let a small amount of water compound into a BIG problem. Drain the road in small amounts early and often.

8. Work From The Top Down vs. Bottom Up

This goes hand in hand with the preceding principle. Address drainage issues starting from the top of the watershed down towards the bottom – don’t start from the bottom up, or you’ll be designing massive (i.e. very expensive and typically ecologically destructive) drainage treatments when you could have been installing much smaller elements distributed throughout the road and its watershed. A top down approach will be better for the entire ecosystem as flows will be dispersed regularly in small amounts the whole length of the road.

9. Maintain Vegetative Cover In Drainage Areas And Receiving Areas

Vegetation is critical to help water infiltrate before it has a chance to run off the landscape and once it has been discharged from a road surface and spread over the receiving landscape. Perennial vegetation is also critical in preventing future erosion, whether from the direct impacts of rain droplets or during a high-discharge event (most often these two things happen nearly simultaneously).

10. Put The Water To Work

Drainage water can be a tremendously productive resource if it is planned for. It can be used to passively irrigate pastures, be directed into ponds, and used to rehydrate broad acreages if properly dispersed (using structures like swales, infiltration basins, and other flow dispersing structures like media lunas). It can literally be as good as dollars in your pocket – dollars that will continue showing up with compound interest year after year.

2 responses to “Vehicle Access Fundamentals For Regenerative Landscapes – First Principles”

[…] First Principles Of Resilient Access Planning And Drainage Design […]

[…] Vehicle Access For Regenerative Landscapes – First Principles ~ the basic principles that guide planning and implementing vehicle access that has a regenerative effect on your site hydrology and ecosystem function. […]